Enhancing Poultry Gut Health: The Roles of Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Postbiotics

Sonja Eksteen: Operational Nutritionist

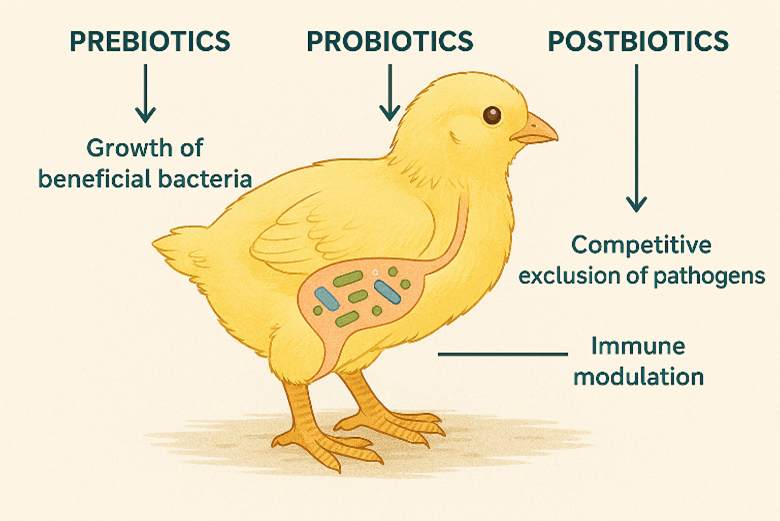

With the global shift away from antibiotic growth promoters in poultry production, the focus has turned to natural alternatives that support gut health and overall performance. Among the most promising are prebiotics, probiotics, and postbiotics—each playing a distinct but complementary role in maintaining a healthy gastrointestinal tract (GIT) in poultry.

Prebiotics are non-digestible food ingredients, typically fibers or oligosaccharides, that selectively stimulate the growth and/or activity of beneficial microorganisms already present in the gut. In broiler nutrition, prebiotics play a crucial role in promoting gut health and overall performance.

The main purpose of prebiotics in Broiler Nutrition is enhancing gut microbiota balance.

Prebiotics encourage the proliferation of beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, which can outcompete pathogenic microbes like Salmonella and Clostridium.

Prebiotics indirectly improves nutrient absorption. A healthier gut environment leads to better digestion and absorption of nutrients, which supports growth and feed efficiency.

Prebiotics boosts immune function by supporting a balanced microbiome. It modulates the immune system, making broilers more resilient to infections and stress.

As part of antibiotic-free production strategies, prebiotics serve as natural alternatives to promote health and performance without relying on growth-promoting antibiotics.

The most common Prebiotics used in Poultry Feed are Fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS), Mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS), Inulin and Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS)

Oligosaccharides (e.g., xylo-, fructo-, and galacto-oligosaccharides) are the most studied prebiotics in poultry. They are derived from non-starch polysaccharides (NSPs) and fermented primarily in the caeca. Fermentation produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which serve as energy sources, lower gut pH and inhibit pathogenic bacteria.

Probiotics are live, non-pathogenic microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer health benefits to the host. The main function in Poultry is to modulate gut microbiota by promoting beneficial bacteria (e.g., Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Saccharomyces) and suppressing pathogens like Salmonella and E. coli. Probiotics enhance the gut barrier integrity by stimulating mucin production and tight junction proteins. Probiotics regulate immune responses, increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-10) and reducing pro-inflammatory markers (e.g., IL-6, IFN-γ). Probiotics improve nutrient absorption and feed efficiency, leading to better growth performance.

Probiotic spores are a specialized form of probiotics—specifically, they are dormant, highly resistant forms of certain bacteria (usually Bacillus species) that can survive harsh conditions like heat, acidity, and feed processing. Once ingested by broilers, these spores germinate in the gut and become active, exerting beneficial effects similar to conventional probiotics. Common Spore-Forming Probiotic Strains are Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus coagulans and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens

Postbiotics are bioactive compounds produced during the fermentation process by probiotics. Unlike probiotics (which are live microorganisms), postbiotics are non-living microbial products or metabolites, such as enzymes, peptides, organic acids, cell wall fragments, and short-chain fatty acids, that still offer health benefits to the host.

The main purpose of postbiotics in broiler nutrition is to support gut health. Postbiotics help maintain intestinal integrity and reduce inflammation, promoting a healthier gut environment. Postbiotics have antimicrobial activity. They contain substances like bacteriocins and organic acids that inhibit the growth of harmful pathogens such as Salmonella, E. coli, and Clostridium perfringens.

Postbiotics can stimulate immune responses by interacting with gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), enhancing disease resistance. Postbiotics can improve feed efficiency by supporting gut function and reducing subclinical infections. Unlike probiotics, postbiotics are not sensitive to heat or storage conditions, making them ideal for pelleted feed and long-term use.

Postbiotics are increasingly used in antibiotic-free programs as safe, stable alternatives to promote health and performance.

Examples of Postbiotic Compounds are Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetate, propionate, butyrate, Bacteriocins (antimicrobial peptides), Peptidoglycans and lipoteichoic acids (from bacterial cell walls) and enzymes and vitamins produced during fermentatio

Tabulated summary of Pre- Pro- and Postbiotics:

| Feature | Prebiotics | Probiotics | Postbiotics |

| Definition | Non-digestible ingredients that feed beneficial gut bacteria | Live beneficial microorganisms | Non-living microbial metabolites |

| Mode of Action | Stimulate native beneficial microbes | Introduce new beneficial microbes | Deliver bioactive compounds |

| Stability | Highly stable | Sensitive to heat and moisture | Very stable |

| Examples | MOS, FOS, Inulin | Lactobacillus, Bacillus subtilis | SCFAs, bacteriocins, enzymes |

| Benefits | Gut health, nutrient absorption, immune support | Pathogen exclusion, immune modulation | Antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, feed efficiency |

.png)